We’ve chatted about CV mixing and audio mixing, but as your system grows, you may find that you need something more advanced to bring all your sounds together and balance them at levels that you find pleasing, rather than just jamming them all together as they come out of the module. System mixers tend to be larger modules that can accommodate many inputs, pan them, change their levels, and combine them together. Often, they’ll have routing features that help integrate effects modules and aid in performance. In a smaller system, a submixer like Xer Dualis can suffice for all of your mixing duties: submixers tend to have a lower number of channels and less routing and channel options. In large systems submixers can be used in conjunction with system mixers to perform more complex mixing duties, too.

Today, we’ll demystify some common mixer functions and chat about what features you may need in your system.

What is a mixer?

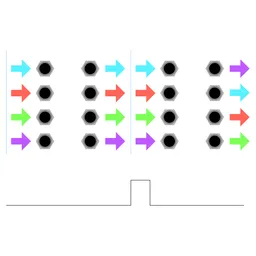

Mixers are utility modules that combine many signals into one signal. Mixers are split up into channels: each channel can modify one signal, and then mix it in with the other signals. Mixer channel controls vary by module, but generally on a stereo mixer, each channel will have a level control that sets how loud the input is, and a pan control that changes the position of the sound from left to right. Mixers often have send controls per channel, too, used to route a channel through effects: we’ll chat more about those later.

Small, medium, large

In Eurorack, as with any other function, there are a huge number of different mixers. When I first built a Eurorack system, I didn’t want to dedicate much space to mixing. It’s quite a utilitarian task, and investing a lot of HP in a mixer just didn’t seem like a good time. However, bringing a hands-on mixer into a system can be a complete gamechanger. Especially if you enjoy performing, mixers end up being a case centerpiece. Mixers are key in DJ performances, for example, as controlling levels is one of the most important parts of building a set. In Eurorack, the same concept applies with even more granularity; a big mixer gives us individual control of each of our patch elements, allowing us to evolve a performance over time in big ways. The mixer in my system is probably my most used module.

The challenges of channels

When picking out a mixer for your system, choosing one that’s big enough for your system is often the hardest part. You’ll want to make sure it has a separate input channel for each voice whose level you want to control. You may also want to think about what effects you have and how you want to use them. If you want to be able to send several of your voices to a single effect without having to change patching, then you may want inputs for your effects. More on this in the Aux sends and effects section.

Many mixers have a mix of mono and stereo channels, so you’ll also want to keep track of the output needs of your modules, too. If you have a percussion-focused system, a mono mixer often does the trick – however, if you like delays and reverb, or those wonderfully wide stereo oscillators, you’ll need a lot more stereo inputs.

If your mixer has pan controls, it’s possible to use two mono channels for one stereo signal. However, you lose the ability to control the level of that signal with a single control, which can be a big disadvantage in a jam.

In my system, I use a mixer with 10 channels: four for percussion, four for melodic voices, and two for effects. Many of my voices and all of my effects are stereo, so picking a mixer with lots of stereo channels was a big priority for me. It’s better to have too many inputs than too few!

Mixing and routing

Along with combining all of your voices into one stereo signal, mixers can greatly expand the capabilities of your effects modules. If you have a single reverb module, but want to use it on three of the sounds in your mix, aux sends are your friend.

Aux sends and effects

Aux sends (aux is short for “auxiliary,” not these guys) are a way to route a subset of channels to a single effects processor. Aux loops create a separate mix of sound that only goes to the effect. The effect is then routed into the main mix and combined with the rest of the sounds. If your mixer features aux loops, channels will have send amount controls that adjust the volume of each sound in that submix. This makes it possible to have, for instance, one lead be drowned in reverb, with a little bit of reverb added to some hats and snares, and a kick drum left untouched. Many mixers have multiple effects loops: a common setup is to have a reverb on one aux loop and a delay on the other, covering all your atmospheric bases. Effects like distortion and compression are fun to experiment with, too, and can give your mix a completely different attitude.

The big advantage of using aux sends is that you aren’t limited to having your effects processor be on either one single channel or over the whole mix. You can use one module to affect multiple channels in different amounts.

When an effect is used in an aux loop, it’s generally best to set dry/wet blend controls to fully wet – that is, they should only output the processed signal, and none of the original signal. The main mix already contains your original unprocessed signal, so having a 100% wet effects loop allows you to use the aux send controls of each channel to control your effects balance without changing the levels of sounds in your mix.

It’s worth mentioning that effects returns – the input that corresponds to an effects send – is just another input channel on your mixer, often with slightly stripped-down functionality. If you need another input in a pinch, an effects return is your friend!

Pre vs. post

Often, mixers will have channel settings that change whether aux sends are pre fader or post fader. This is an option that changes whether or not the volume fader of a channel affects how much the signal is set to an effects loop. When set to pre, the effects send is before the fader, and the fader doesn’t change the level of the sound going to the effects loop. When set to post, the fader affects the level of the effects send, too.

In my patches, I tend to use post-fader sends, as they make mixing a bit more straightforward. However, pre-fader sends allow for some interesting techniques, like bus processing. Let’s say you have a few drum voices that you want to run through a compressor, but you don’t want to put the compressor after the mixer to process everything. You can put the compressor in an aux loop, route your drum sounds to them using the send controls, and turn their levels all the way down – and as long as you’re using a pre-fader send setting, you can control their level in the mix with their respective send controls.

Mix things up: mute, cue, and CV

Many larger mixers will have extra features that aid in patching and live performance. The features that matter to your needs will vary depending on your application, but they’re always worth considering, especially if you’re a performer (or plan on performing down the line) or just enjoy jamming in your living room for your cat.

Mute

Mute controls are a simple and effective option to have: they make it easy to take a sound out of the mix with a single control. The advantage of a dedicated mute control is that you can take an element out of the mix, then bring it back at exactly the same level.

Nifty.

Cue (not Q, that’s a filter control)

Cue is a performance-oriented feature that allows a signal to be previewed in a set of headphones or monitors before it’s sent to the main mix. This is useful if you need to re-tune a voice on the fly, or want to hear how an element sounds against the rest of the mix before your audience does.

CV control

CV control over a mixer can be surprisingly helpful, and can help you save space in your system, too. CV over level is particularly helpful in a small rack: let’s say you’re patching up a voice using a freerunning oscillator and you need a VCA to control its level. If you have CV control over channel level, your mixer can act as a VCA for that voice, too – you may not need a big VCA in your system at all.

CV over pan is also a relatively common feature, and is a fun way to add gentle movement, create dizzying patches with LFOs, or create Leslie-speaker effects with audio-rate CV modulation. Dedicated panning modules tend to be large, so having this feature built into your mixer is another great way to save space.

Outputs

Once we’ve put a mix together, we need it to go somewhere so we can hear it. Some mixers have different output types built in, but a majority will just have a pair of stereo Eurorack outputs. Pairing a mixer with an output module is helpful if you plan on performing, or want to use headphones with your system, or need to connect a set of monitors directly to your rack.

However, if you’re just recording your system to an audio interface or portable recorder, you can often patch the mixer outputs directly to your recorder, and use the master level control of the mixer (or a pair of attenuators) to set the mix to an appropriate level for the next device in your chain.