Welcome back to Getting Started, the series where we explore the fundamental types of Eurorack modules and discuss what they do, how to use them, and how they fit into a system. And of course, it wouldn’t be a Noise Engineering blog without some wackiness, so at the end of each post we’ll discuss a more advanced/abstract/unusual technique for each type of module for you more experienced patchers out there.

In our last episode, we talked about modulation and CV mixing. Today, we’ll be discussing a few other ways that we can modify CV and open up new possibilities in our patches. These are a bunch of relatively simple concepts, but they’re very important: they open up an extra level of precision and versatility in modules that you already have in your system.

MULTS

Mults don’t really modify CV, but they are incredibly handy, and deserve a mention here. Mults, short for “multiples,” take in one signal and split out multiple copies of that signal.

There are two types of mults in Eurorack: passive and active. Passive mults are unpowered, and copy a signal into many signals. Active (sometimes called “buffered”) mults require power and have some circuitry on them to allow the copies they make of an incoming signal to be a bit more precise… which sometimes you need, but often you don’t! Let’s explore the pros and cons of each.

Passive mults can be modules, cables, or dongles. They don’t take up power, which is nice, and in the case of cables and dongles, they don’t even take up rack space. These are great for multing things like gates, envelopes, and CV that isn’t pitch related. The downside of passive mults is that you can sometimes get what’s called signal “droop” or a little bit of loss. In most cases, this “droop” is really small and not a problem, but if you’re splitting a sequence that is meant to go to pitch inputs, this can make a big difference: you may notice your patch go out of tune a tiny bit. Our ears are amazingly sensitive to pitch differences!

The “active” in active mults means they require power. The power drives some circuitry that prevents the small amount of droop that you can see in passive mults, so you can make lots of copies of a signal with virtually no loss. This means that active mults are better for splitting CVs where precision really matters, like pitches.

Oh, and you can mult audio too -- that’s a concept outside the scope of this post, but don’t be afraid to experiment!

ATTENUATORS

Mults are handy, but they don’t change our CV, they just give us more copies of a signal. The most simple and common way to actually modify CV is to attenuate it, or make it smaller. Let’s say that we’re modulating a filter with an LFO: we may not want to sweep the entire frequency range of the filter, so by using an attenuator on the LFO we can bring its voltage range down and make it modulate a smaller amount of the filter’s frequency range. This allows us to fine tune our modulation, and makes it easier to create patches that do exactly what we want them to.

INVERTERS

An inverter turns a CV signal upside-down. Let’s say that we have an envelope, but instead of having it open a filter, we want it to close the filter. We could invert that envelope, and instead of going up, it would go down instead. This is a technique that’s less commonly used in isolation than attenuation, but is sometimes quite helpful.

COMBO MEAL: ATTENUVERSION/POLARIZATION

Often, attenuators and inverters are combined into something called an attenuverter (attenuator-inverter), sometimes referred to as a polarizer. Generally, these will be bipolar controls: above 12:00, they attenuate, and below 12:00 the invert and attenuate. That means that you can set the level and polarity of a signal however you want with a single knob!

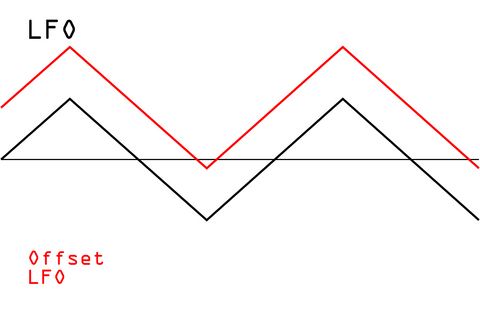

OFFSET

Offsets are a way of changing where a CV baseline is. Let’s use an envelope generator as an example: if our envelope starts at 0 volts and peaks at +5 volts, but we offset it by +3 volts, it would start at +3 volts and peak at +8 volts.

Now, this can get a tiny bit more complicated, because many Eurorack signals are bipolar. What’s that mean? Imagine we have an LFO, and it cycles from -4 volts to +4 volts, centered around 0 volts. If we offset it +2 volts, it would now cycle from -2 volts to +6 volts, centered around +2 volts. Offsets are useful for a number of things: Eurorack modules use a variety of different voltage ranges, and you can use offsets to help make one module’s CV output range work more effectively with another module. You can also use an offset as a performance parameter, changing how modulation affects a destination on the fly.

MIXING AND PRECISION ADDERS

In our last post in this series, we talked about mixing CV. That’s a very useful form of CV modification, as it lets us combine multiple CV sources into a single signal. However, mixers are usually slightly imprecise, which means that they won’t always be accurate for things like pitch CV. That’s where precision adders come in. The first thing you’ll notice about precision adders is that they are more expensive than other CV mixers. This is because they are built with parts that are a lot more precise than your average CV mixer -- but precision comes at a cost and these parts are expensive! Precision adders allow you to do things like transpose one pitch sequence with another pitch sequence. If that’s not something you’re looking for, you can save a bit of budget by choosing a regular CV mixer for your system.

Regular mixers work great for signals that don’t need to be quite as precise, like envelopes: one of my favorite techniques is to run a few envelopes into a CV mixer, and set them all to different levels. This creates a single complex CV signal that will do really interesting things to its CV destination! Let’s take a listen to what that technique can do. Here, we have a sine wave run through a wavefolder, and a mixture of four decay envelopes modulate the wavefold amount:

VOLTAGE-CONTROLLED ATTENUATION/ATTENUVERSION/OFFSET

Modular is all about modulation. Sometimes, when we modify CV, we don’t want that modification to be static: we want to be able to modulate that modification. Very meta.

For instance, CV mixing is effectively voltage-controlled offset: you can think of one signal as offsetting the other when you mix them together. I tend to mix slow signals with faster signals so they evolve over time: it’s a nice way to create some subtle variation in a patch

We can create voltage-controlled attenuation with most VCAs. A really common patch involves an LFO run through a VCA, which is opened and closed by an envelope. The envelope controls how much the LFO modulates its destination, creating an evolving modulation signal each time the envelope is triggered.

Voltage-controlled attenuversion, however, is a bit more unusual, and will generally be done with a dedicated utility. A module like this can act similarly to a VCA, but it can also invert signals based on the strength of an external CV signal. These generally belong in more complex patches, and are a little more niche than the other modules we’re discussing here, but they still offer some interesting patching options: for instance, you could use an LFO to change the strength and polarity of an envelope, making it change whether it opens or closes a filter or other CV destination over time.

Let’s take a listen to one of these techniques in action. Here, we’ve run an envelope generator through a VCA, which is controlled by an LFO. The resulting signal modulates a filter. The LFO changes how much the envelope opens up the filter, which gives us variation as the patch plays.

BUILT-IN: HOW MODULES PROCESS INCOMING CV

Many modules have built-in CV processing. For instance, on most of our modules, a CV input’s corresponding knob will offset the CV input. Some modules feature attenuators and attenuverters right in the module. And some modules offer multiple CV inputs that modulate the same destination, which gives us onboard CV mixing. It’s good to check the manual for whatever module you’re modulating to learn how it processes incoming CV -- this will make it easier for you to control your patches and get the results you expect.

Techniques like we’ve talked about here sometimes appear in a more complex module’s internal structure, too: multing and modifying modulation is the basis for the internal modulation structure of our Percido oscillators. They take a single envelope and mult and attenuvert it to multiple destinations. This means that even though we only have one source of modulation, it can do a whole lot of different things.

While many modules have some way to modify incoming signals, it’s unusual for them to feature attenuation and inversion and offset AND mixing all built in. That’s why having utilities in your system is useful: there are always different uses for CV modification in a patch, and having the modules to make the changes you need on hand is always helpful.

FOR ADVANCED PATCHERS: GATES

Did you know that you can use gates as modulation signals? It’s a fantastic technique for creating rhythmic modulation: a gate sequencer or a clock divider can be patched directly into other modules, or processed with something like a CV mixer or attenuators for even more complexity and control. I use this technique quite a bit for modulating percussive elements or adding accents to a synth line. It’s a simple concept, but it can also create some pretty incredible and complex results when used to CV things like wavefolders and filters.

Looking for modules?

Here are just a few modules that can perform some of the functions we've been chatting about. There are always lots of choices in modular!

2hp Mult: A small passive multiple.

2hp Buff: A small active multiple.

Noise Engineering Sinc Defero: Quad attenuator and multiple.

Noise Engineering Roti Pola: Mixer, offset, attenuverter.

Noise Engineering Quantus Ampla: Quad VCA and mixer.

Mutable Instruments Blinds: Quad voltage-controlled attenuator/inverter.